An introduction to Webmercator

Introduction

The Mercator projection has been around for almost 500 years. During its history it has seen many roles. It started as an answer to the needs of naval navigation, continued to the de facto projection used in atlases, and now the mercator projection has experienced a new dawn in the form of webmercator, arguably being as relevant as ever. Map projections can be a tricky subject. I have written this article to hopefully give myself some clarity concerning the topic. In this article I am going to go through how a mercator and more specifically web mercator map is formed and what makes a web mercator map differ from a normal mercator map. A basic understanding of trigonometry and calculus is recommended.

Projecting from a globe to a 2D surface is a funamental problem in cartography. It is not possible isometrically (without any distortions), therefore a map is always a compromise, usually focusing on one key metric that it displays truthfully. Common metrics that cartographers are interested in are distance, area, shape and direction. The mercator projection is classified as a conformal projection, meaning it retains direction but not distance or shape. This causes a straight line on a Mercator map would be a loxodrome (also alled rhumb line) on the globe.\

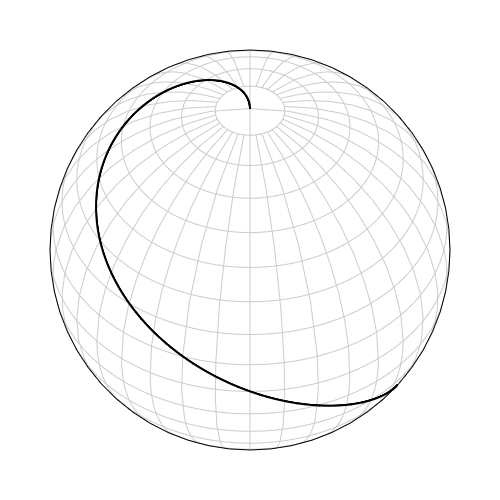

A loxodrome running from pole to pole:

This is optimal in seafaring, because you can easily see where you will end up when you keep a certain bearing. As a downside it does not display areas uniformly; areas are enlarged the closer to the poles one goes. This has caused critique towards the Mercator projection, because it shows espcially Europe to be grander than it is in relation to for example Africa. I would argue that atleast in the 16th century the mercator projection was created as a solution to a relevant naval problem and not as nationalistic propaganda.

An other handy feature that comes with conformity, is that since Mercator retains direction, it means that north is always up on the map. This might sound funny since we are so used to conformal projetions nowadays. In addition all parallels and meridians are straight lines.

Scale factor

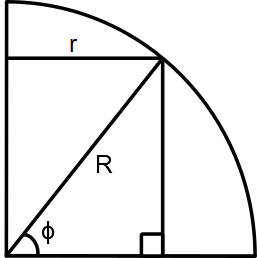

To retain conformity we want that at all positions on the map, the length of one degree longitude is equal to the one degree latitude. The distance of one degree of latitude is constant wherever you are, because all lines of constant longitude (meridians) are great circles with a length of 2πR. Lines of constant latitude, (parallels), are not great circles, except for the equator. The length of the parallel is equal to the length of the equator times the cosine of the latitude (2πRcos).

We now know what the length of a parallel is at a given point, and now we want to determine how to map the lat/lon values to coordinates of x and y on a map. In a mercator map the origin of the map (point 0,0) is located at the center of the map, giving us a potential coordinate range of ([-90,90],[-180,180]). The x-axis is the equator and the y-axis is the prime meridian. The length of the x axis is 2πR and we need to determine te length of the y axis. To determine this we need to calculate the so called scale factor of a given parallel. As defined earlier, a given latitude has the length of 2πRcos. Therefore to get each parallel to a length of 2πR we need to multiply the length of the parallel with 2πR/2πR cos(x) = 1/cos(x). The inverse of the cosine is also called the secant (sec(x)=1/cos(x)). Now we get to the mathematical beef of the mercator projection. To get the scale factor of a parallel at lat x, we need to sum all of the 1/cos(x)s along the way. If one has studied calculus, it is now clear that this can be achieved with an integral: ∫sec(x).

The integral of the secant

Calculating the scale factor and therefore the integral of the secant has been historically the main problem to solve with the mercator projection, and its discovery is a rather interesting story. I plan to write its own dedicated blog post about it, but in the meantime, you can check this excellent blog post by Lior Sinai about it.

Let's derive the formula for the integral of the secant, because at least for me it is not that intuitive. There are several ways to derive the formula (most notably substitution, partial fractions, trigonometric formulas, hyperbolic functions). For me the substitution method has always been the easiest to grasp:

We will use substitution u = sec x + tan x.

Since the derivatives of sec x (sec x tan x) and tan x (sec^2x) have sec x as a common factor, we get

du = sec x tan x + sec^2x.

Now:

∫ sec x dx

= ∫ sec x (sec x + tan x) / (sec x + tan x) dx

= ∫ (sec^2x + sec x tan x) / (sec x + tan x) dx

Substituting u in the above integral we get

∫ du / u = ln |u| + C

And now substituting u = sec x + tan x back we get

ln |sec x + tan x| + C\

In addition to ln | sec x + tan x | C the integral of the secant posesses two other equivalent trigonometric identities: ½ ln((1+sin x)/(1-sin x))+C and ln | tan (x/2 + π/4) |. Usually the identity that is most convenient is used (as demonstrated in the example below)

Differences between merator and webMercator

If you have been paying attention, you might now mention that yes this works on a globe that is perfectly round, but the Earth is not a perfect sphere, but instead an ellipsoid, being slighlty flattened on the poles and bulged at the equator. The mercator projection does take this into account but instead webMercator does not. This wouldn't matter otherwise, but webMercator requires its coordinates to be in WGS84 which assumes a ellipsoid earth. This causes the webMercator to be slightly non-conformat. The distortion is larger the closer one is at the poles. For this reason for example the US Department of Defence does not accept webMercator to be used in any official use.

I mentioned earlier that by placing the origin of the map at (0,0), we have a potential coordinate range of ([-90,90],[-180,180]). However as the scale factor approached infinite as the absolute value of latitude approached 90, we need to cap the range of the y-axis to a certain value. Internet map clients usually display their maps as square tiles. The tile at zoom level 0 coveres the entire world. Therefore in webMercator such coordinates are chosen that the resulting map is a square. This can be calculated by solving x of 2πR = 2Rln|tan(π/4 + x/2)|:

2πR = 2Rln[tan(π/4 + x/2)]

π = ln[tan(π/4 + x/2)]

e^π = tan(π/4 + x/2)

arctan(e^π) = π/4 + x/2

x = 2arctan(e^π) - π/2 ≈ 85.05112878°\

So if we want to display the globe as a square in a spherical mercator projection, we need to cap the y-axis to ±85.05112878°.

Another thing to consider with webMercator is that it's origin is not in the center of the map, but in the top left corner. This is because in many instances in web development, the origin of elements is at the top left corner.

As mentioned, mercator and webmercator is not perfect, but it is still used in most pospular web map applications. If you have read all the way through, thank you for reading, any comments are always welcome.